A Bookish Tour Through the Cathedrals of England

England really is a book lover’s playground, isn’t it? There are cozy little bookstores and charity shops on every high street, charming villages straight out of Agatha Christie novels (with slightly lower murder rates, thank goodness), and lovely literary blue plaques and markers all over the countryside.

I just love it. Book history is everywhere. And of course, the country’s houses of worship are no exception. They are filled with literary history. So often when I tour the churches and cathedrals of England, I find myself echoing Kathleen Kelly in You’ve Got Mail, “So much of what I see reminds me of something I read about in a book…”

(Of course, she goes on to say “…when shouldn’t it be the other way around?” to which I saw PSHAW. It’s not one or the other.)

So here’s a little tour of English cathedrals for book lovers. Enjoy, and happy weekend! xo

{Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey}

I’ll start my tour of English cathedrals with the only church on this list that is NOT a cathedral. It is, however, a very large church, and a very famous one…possibly the most famous church in England?…so I hope you’ll forgive me for bending the rules a bit.

A visit to Westminster Abbey can feel a bit like a visit to a circus. It is jam-packed with tourists (which you really have no right to complain about because you are one, too), and visitors are encouraged to follow a maze of a path past all of the major tombs. Isaac Newton? Check. Queen Elizabeth I? Check. Move on to the next.

Poets’ Corner is a little bit of an oasis of calm at the end of the maze.

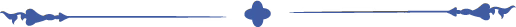

Geoffrey Chaucer was the first writer buried in this area of Westminster Abbey - not because he was a poet, but because his day job was Clerk of the King’s Works. Almost 200 years later, the poet Edmund Spenser asked to be buried near Chaucer, and the tradition began.

There are two types of monuments in Poet’s Corner: the tombs of writers who are buried there and memorials to writers who aren’t, but who are considered important enough to English literature to deserve a mention. It can be disconcerting at first because it’s not entirely clear which is which. Wait, you say, didn’t I just see Shakespeare’s grave in Stratford-upon-Avon? You did, his monument here is just a reminder that he was a great English writer.

The Dean of Westminster decides who is buried in Poets’ Corner and who isn’t, and who gets a memorial and who doesn’t. George Eliot famously requested burial in Poets’ Corner, but was denied because she was in a long-term relationship with a married man. She was allowed a memorial in 1980, which seems a bit like the literary equivalent of the Pope deciding that the Catholic Church may have been wrong about Galileo 300 years after his death.

T.S. Eliot is the only American with a memorial plaque here. He was offered burial at the Cathedral, but had made other plans in his will. He would have been the only American buried in Poet’s Corner - he’s now the only American with a memorial plaque here.

(There are people who will claim that T.S. Eliot is British, but there are also people who will claim that Henry James is British, which is pure lunacy. T.S. Eliot was born in Missouri, and it doesn’t get more American than that.)

If anything, a stroll through Poets’ Corner is a reminder of the incredibly deep and rich history that is English literature. It’s a wonderful place to start your tour.

{York Minster}

Ah, the beautiful front facade of York Minster. “The Minster”, as it’s known locally. It is in front of this facade, on a snowy February morning in 1807, that the Learned Society of York Magicians gathers in Susanna Clarke’s novel Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell.

“They were gentleman-magicians, which is to say they had never harmed any one by magic - nor ever done any one the slightest good. In fact, to own the truth, not one of these magicians had ever cast the smallest spell, nor by magic caused one leaf to tremble upon a tree, made one mote of dust to alter its course or changed a single hair upon any one’s head.”

The magicians of the Learned Society were theoretical magicians, you see, not practical magicians. But they have been invited here, to York Minster, by Mr. Gerald Norrell, who claims that he can prove that practical magic is alive and well in England. And if he can, the Learned Society of York Magicians will be forced to disband forever, and each member will be impelled to give up their theoretical study of magic.

Does he prove it? Does Mr. Norrell make magic happen? You’ll have to read the book to find out. And then you’ll have to read the next 800 pages, to find out what happens after that.

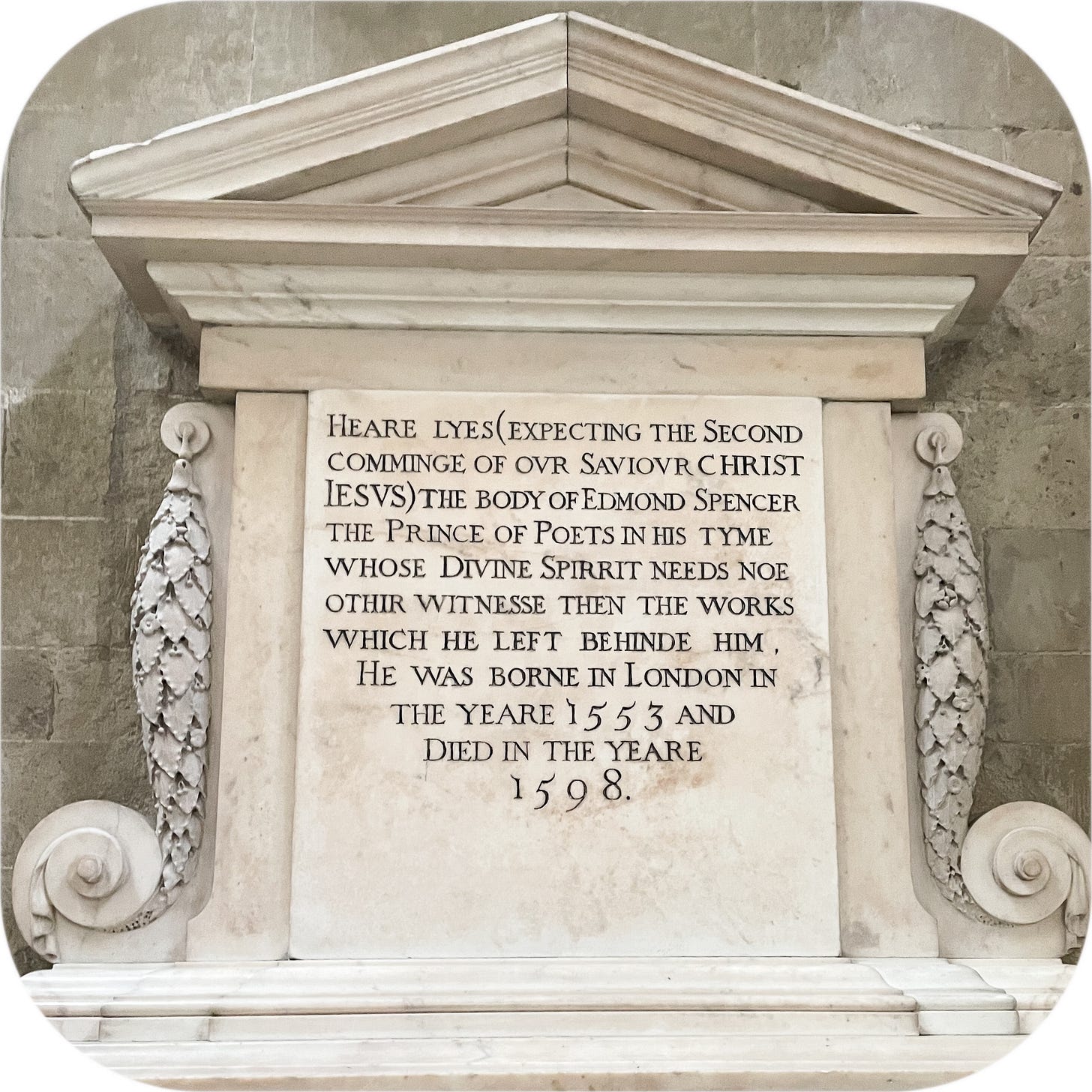

{Durham Cathedral}

There are few sights as lovely as the view of Durham Cathedral on its hill from across the river below. The writer Bill Bryson was Chancellor at Durham University from 2005 until 2011, and he declared, “I unhesitatingly give Durham my vote for best cathedral on Planet Earth.”

(I happen to agree. Best cathedral in England, at the very least.)

But Bill Bryson is not the writer who should draw you to Durham - or not the only one anyway - because enshrined in a tomb in the Galilee Chapel are the remains of the Venerable Bede.

It’s always struck me as a funny name, to be honest. You never hear Bede, or St. Bede…it’s always the Venerable Bede. But who was Bede, and why was he so venerable, anyway?

Born around 673 AD, Bede is one of history’s great polymaths. A scholar of history, religion, astronomy, mathematics, and language, his Ecclesiastical History of the English People is one of the most important primary sources of Anglo-Saxon history and of the early Christian Church in England. In fact, we refer to the year Bede was born as “673 AD” because Bede popularized the use of Anno Domini as a dating system in his Ecclesiastical History. Durham Cathedral was built in the 11th and 12th centuries in part to house the remains of the Venerable Bede and St. Cuthbert.

So why is he known far and wide as the Venerable Bede, besides his undeniable venerability? According to the Durham Cathedral website, it is simply because his tombstone was engraved with the words Hic sunt in fossa Bedae Venerabilis ossa, or “Here are buried the bones of the Venerable Bede”. Sometimes the simplest explanations are the correct ones.

{Salisbury Cathedral}

“The Rev. Septimus Harding was, a few years since, a beneficed clergyman residing in the cathedral town of ——; let us call it Barchester. Were we to name Wells or Salisbury, Exeter, Hereford, or Gloucester it might be presumed that something personal was intended; and as this tale will refer mainly to the cathedral dignitaries of the town in question, we are anxious that no personality may be suspected.”

So begins Anthony Trollope’s The Warden, the first book of his six-book series set in the fictional county of Barsetshire. Despite Trollope’s insistence in the opening that Barchester isn’t based on any particular English cathedral town, he later wrote in his Autobiography that he was inspired to write his novel after a stroll through Salisbury Cathedral Close one summer evening. And it certainly sounds like Salisbury: “It stands on the banks of the little river, which flows nearly round the cathedral close, being on the side furthest from the town. The London road crosses the river by a pretty one-arched bridge…The entrance to the hospital is from the London road, and is made through a ponderous gateway under a heavy stone arch…”

The dispute at the center of the novel was based on an incident at Winchester Cathedral, where Anthony Trollope had studied as a young man.

{Gloucester Cathedral}

Now we come to lovely Gloucester Cathedral, which has two links to children’s literature. And this is the point where I have to make a confession - a confession that at first may seem completely irrelevant to a tour of English cathedrals. And that confession is that I have never seen a Harry Potter movie, nor, indeed, read a Harry Potter book.

I mention that now because Gloucester Cathedral these days is very well known as one of the filming locations for the Harry Potter movies. From what I understand, scenes were filmed in the cathedral’s gorgeous fan-vaulted cloister, which stands in for the corridors of Hogwarts in some of the movies. But I can’t tell you exactly which ones.

Nearby the cathedral, in a little storefront right next to an arch that leads to the Cathedral Close, is another link to literary history. It is the House of the Tailor of Gloucester, setting of Beatrix Potter’s story of the same name.

“But the tailor came out of his shop and shuffled home through the snow; he lived quite near by in College Court, next to the doorway to College Green. And although it was not a big house, the tailor was so poor he only rented the kitchen.

He lived alone with his cat; it was called Simpkin.”

It is in this house that the poor tailor sleeps off his illness, while some very special little assistants help him to finish the finely embroidered coat he has been commissioned to make for the Mayor of Gloucester’s wedding.

{Winchester Cathedral}

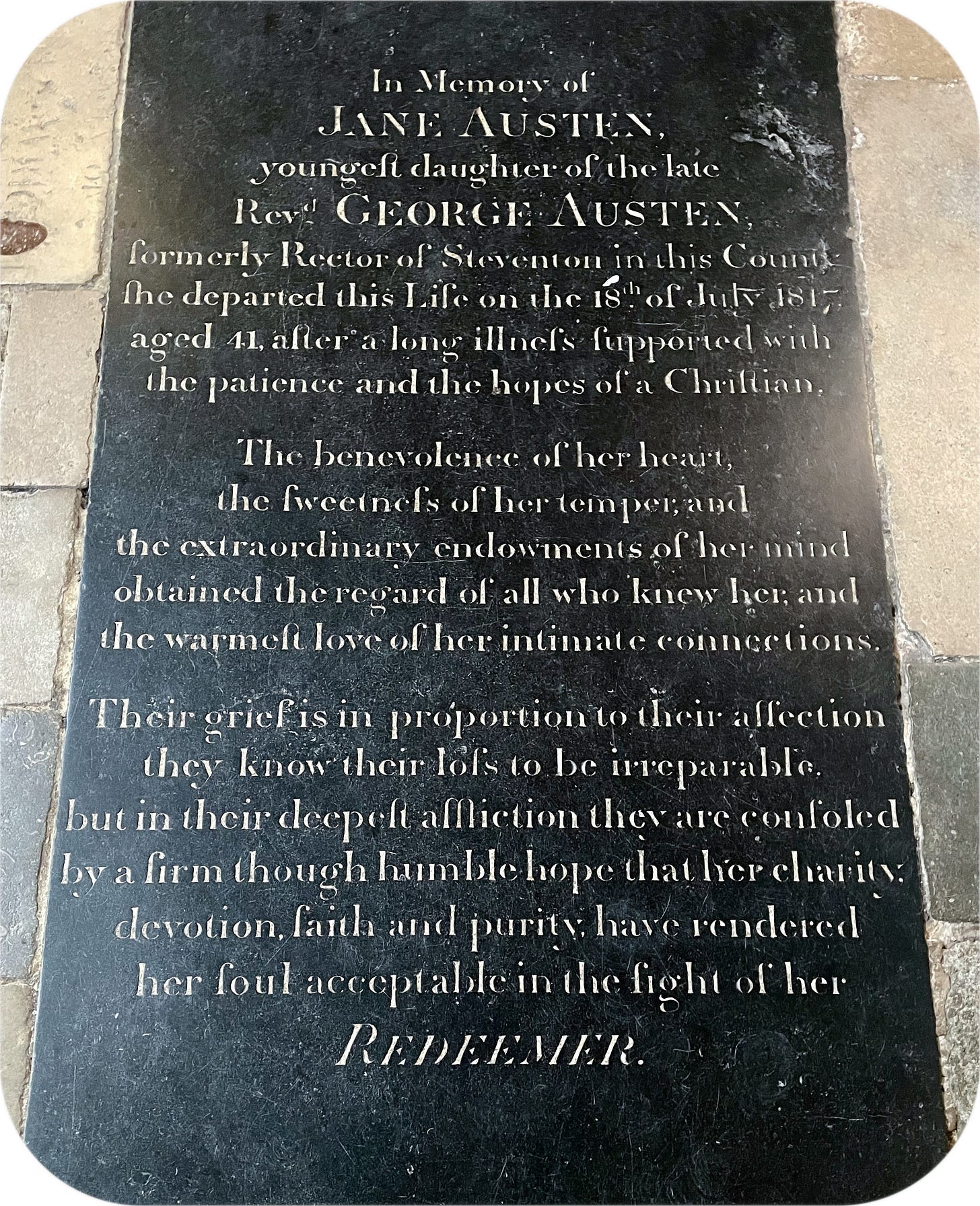

In May, 1817, Jane Austen made the journey from her home at Chawton to the city of Winchester, less than 20 miles away. She was brought by her sister Cassandra and her brother Henry, who hoped that Jane could find the medical treatment that she required, as the illness that had plagued her for over a year grew progressively worse. Jane moved into a house at No. 8 College Street, where she was treated by a physician from Winchester Hospital. Alas, the treatment was in vain. Jane Austen died in the house on College Street just a few months later at the age of 41, of a disease that we’re still not able to definitively identify.

She was buried in Winchester Cathedral, in the north nave. Her epitaph, written by her brother James, reflects her family’s deep grief and reads, in part, "The benevolence of her heart, the sweetness of her temper and the extraordinary endowments of her mind obtained the regard of all who knew her, and the warmest love of her intimate connections.”

It is an extremely heartfelt memorial, but makes no mention of her writing, apart from the allusion to the “extraordinary endowments of her mind”. In 1869, Jane’s nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh wrote the first biography of the author, A Memoir of Jane Austen. A brass plaque was placed nearby her grave, funded by the proceeds of this memoir, that clarifies Jane’s status as a writer.

Isaak Walton, the 18th-century scholar and author of The Compleat Angler - beloved by fishermen worldwide - is buried on the other side of Winchester Cathedral. I stumbled upon his grave while touring the cathedral, but no one else seemed to be paying much attention. It’s hard to be buried near a superstar.

{Canterbury Cathedral}

And then there’s Canterbury.

Canterbury Cathedral: spiritual heart of the Church of England, and home to its leader, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Inspiration for Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales and the setting of T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral…and, of course, the site of the bloody killing that was the basis for both of them.

In 1170 Thomas Becket had been Archbishop of Canterbury for eight years, after having served as Lord Chancellor under his friend King Henry II. Several years into his term as Archbishop, Becket and Henry had a falling out. Becket wanted to assert the Church’s independence from the Crown, and Henry wasn’t having it. After Becket used his power to excommunicate the Archbishop of York and several bishops, all of whom were loyal to the King, Henry was done. Tradition has it that on Christmas Day, he was heard to exclaim in frustration, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest?” Upon hearing this cry, four of the King’s knights traveled to Canterbury, hoping to take Becket prisoner - but Becket ran into the cathedral, desperately clinging to a column to avoid apprehension. In a series of powerful blows, the four knights decapitated the Archbishop. His body lay at the base of the column until the following day, when monks buried him in the crypt of the cathedral.

Shortly after the murder, rumours began to spread about miracles and healings taking place in the name of Thomas Becket. In 1173 he was proclaimed a saint. Shortly afterward, the monks of Canterbury opened the crypt to visitors, and pilgrims began to visit from all over England, in the hopes that the saint’s miraculous healing power would heal them.

Approximately 200 years later, Geoffrey Chaucer wrote a series of twenty four short tales told as stories recounted by pilgrims on their way to visit St. Thomas Becket’s shrine. We know them, collectively, as The Canterbury Tales.

{Wells Cathedral}

On a much happier note, there’s lovely, light-filled Wells Cathedral.

The early 20th-century novelist Elizabeth Goudge was born on the Cathedral Close here, as her father was vice-principal of the Theological College. She set her novel City of Bells here, where the town and cathedral are fictionalized as Torminster, likely due to its close proximity to Glastonbury Tor.

Which is another reason to visit Wells Cathedral - it is also just a hop, skip and a jump away from the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, which of course have strong literary ties as the purported burial site of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere. Although that is up for debate.

{Hereford Cathedral}

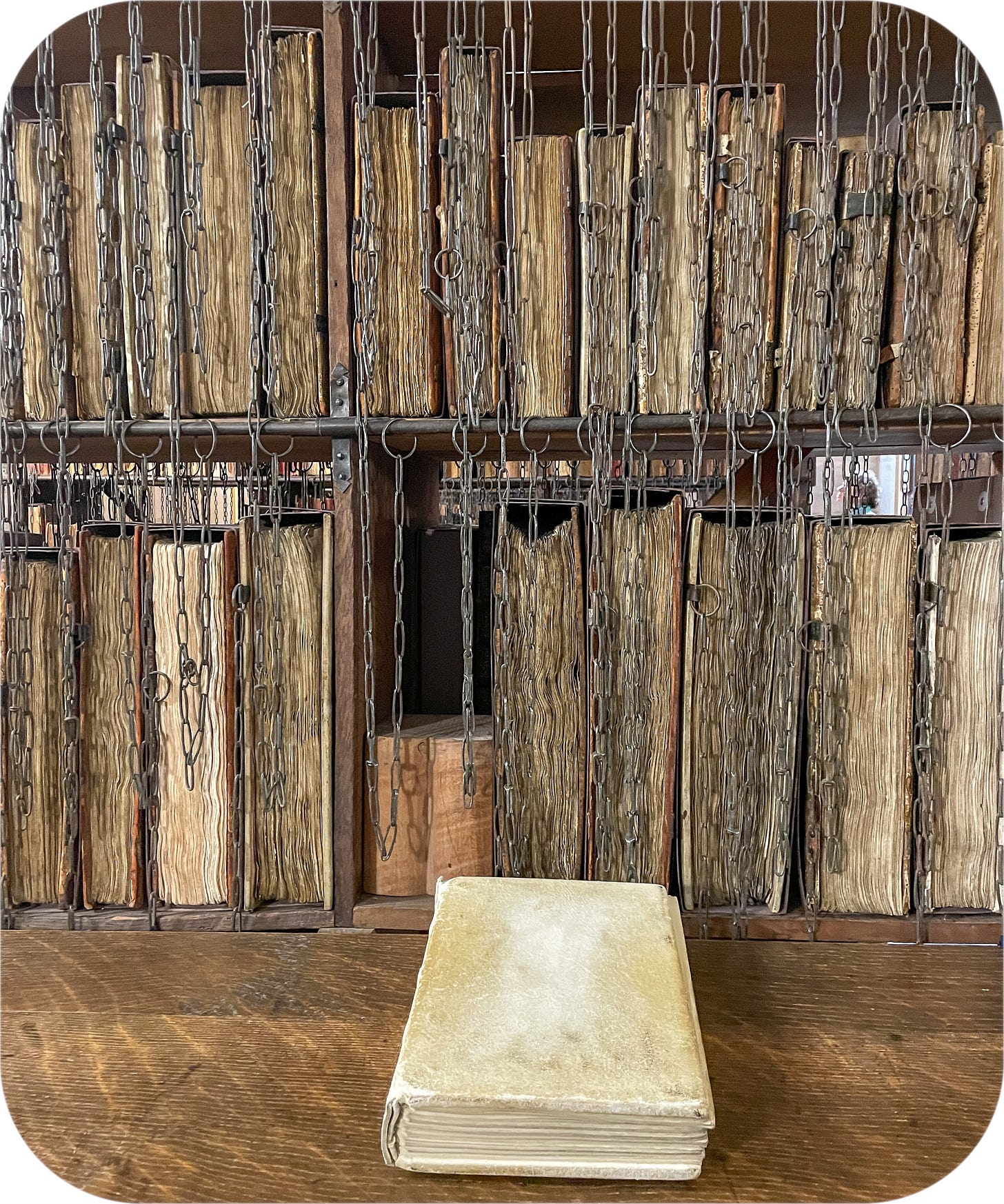

Hereford Cathedral is not, perhaps, the most well-visited cathedral on this list, but those who make the trek to this city close to the Welsh border are in for a very special treat. Not only does it hold one of the four surviving original copies of the 1217 Magna Carta, it houses the Hereford Mappa Mundi - the largest medieval map in existence. More than that, though, unassuming Hereford Cathedral is home to the largest surviving chained library in the world.

Chained libraries were common before the 17th century. Libraries that were open to the public used the chaining system to keep their valuable manuscripts and early printed books safe from theft. A chain was attached to the book via a ringlet at the front edge, and then attached to a rod that ran along the shelf.

Because the books are attached at the front edge, they have to be housed fore-edge out, so that the chain doesn’t damage the volumes next to it, or tangle when the book is withdrawn. Indexes are posted at the end of each row, so that visitors can determine which volume they’re searching for.

Hereford’s chained library includes almost 1,500 early books, including an amazing 229 hand-illuminated manuscripts dating to as early as the 10th century.

Chained libraries became less common in the 15th century, with the age of Gutenberg and movable type. Books became more common, and therefore didn’t have to be quite as fiercly guarded.

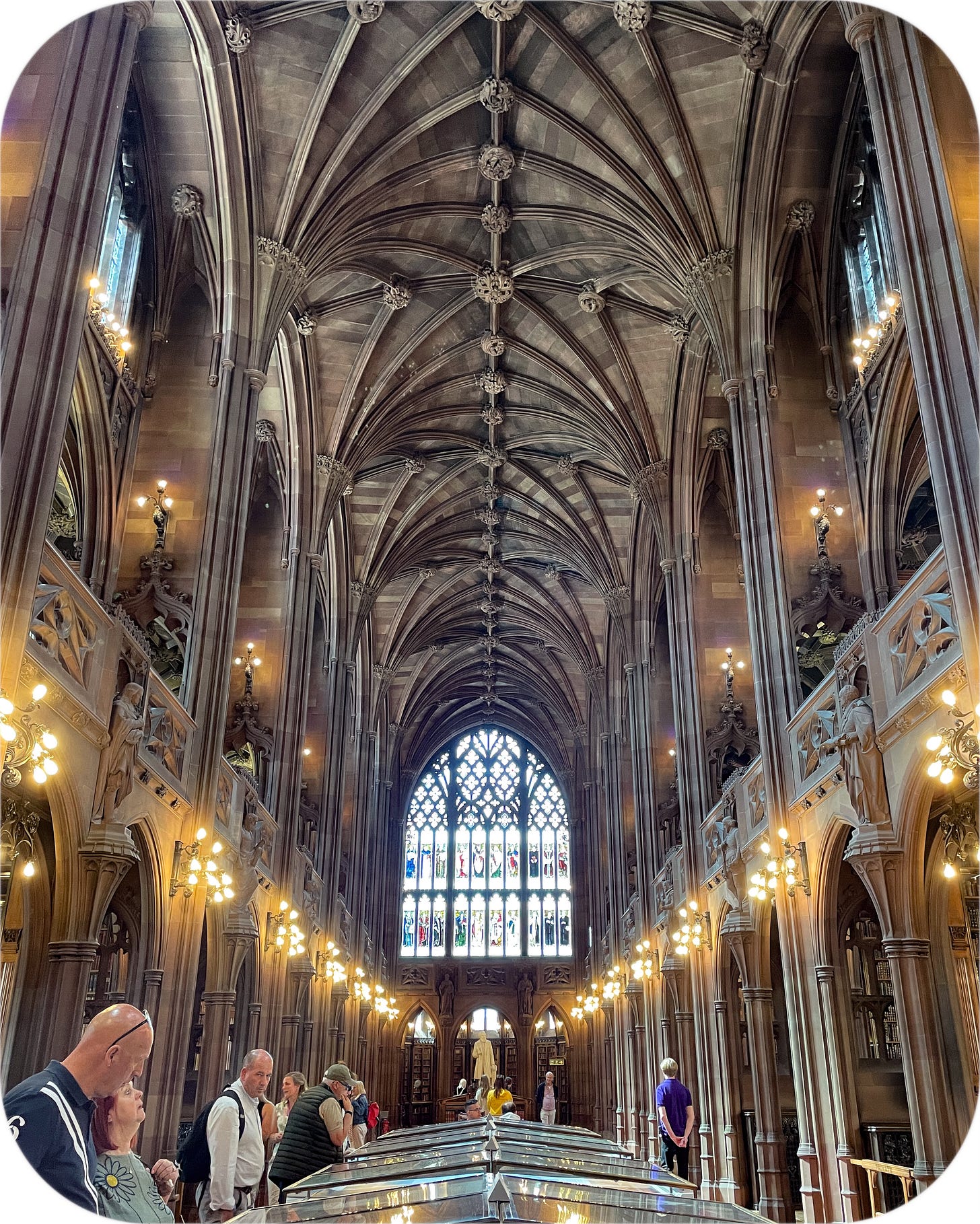

{Honorable Mention, John Rylands Library, Manchester}

Look at that Gothic architecture: the stained glass, the soaring columns, the rib vaults. And then look closer.

Tucked into each little alcove are not pews, but books. This beautiful Victorian Gothic building isn’t a cathedral; it’s a library.

The John Rylands Library opened on January 1, 1900. It was founded by Enriqueta Augustina Rylands, in memory of her late husband, John Rylands, a wealthy cotton manufacturer in Manchester, who had left Enriqueta his vast fortune when he died in 1888. She spent the intervening years collecting rare books and purchasing notable private libraries, including the Althorpe Library from the 2nd Earl Spencer, for which she paid $210,000 - a quite substantial amount of money in 1892. The Rylands Library is now known as The John Rylands Research Institute and Library and is part of The University of Manchester. The gorgeous building stands in the center of Manchester, is open free to the public, and gains honorable mention on our list as a cathedral to literature.

PS - If you enjoyed this tour, please consider becoming a subscriber to have The Diary of a Lady Traveler delivered to your inbox. Subscriptions are free, unless you choose otherwise. If you are interested in reading my previous letters from abroad, visit my homepage: The Diary of a Lady Traveler. Finally, absolutely no pressure at all, but if you’d like to support my writing, I’ve added a virtual tip jar as well: you can find the “Buy me a coffee” button below. Thank you for reading!

Love the history and your incredible photos, Jodi, as usual!!!

A lovely post, thank you for sharing. I’ve been to some of them and John Rylands is a favourite.